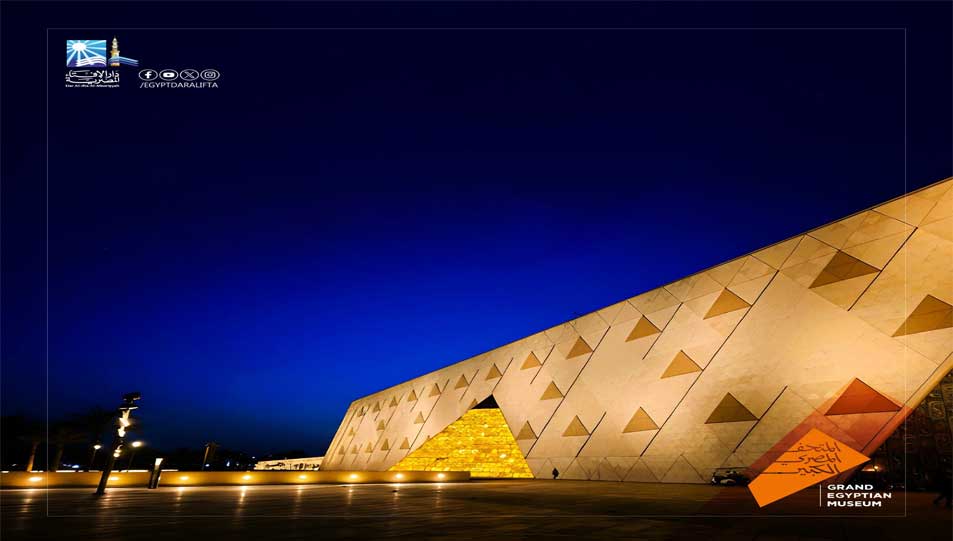

The Grand Egyptian Museum: A National Monument and a Universal Mosque of Knowledge

The opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) marks not only a monumental cultural achievement for Egypt but also an opportunity to reflect on how Islam—as both a faith and civilization—relates to the legacies of earlier nations. This historic event invites deeper contemplation of the Islamic worldview regarding the past. Contrary to modern misconceptions that equate religiosity with the rejection of pre-Islamic heritage, the Islamic tradition has long encouraged reflection, preservation, and moral learning from earlier civilizations. The Qur’an situates human history as a continuous dialogue between divine guidance and human endeavor, framing the study of earlier nations as a form of faith-based inquiry.

Qur’anic Epistemology: Reflection Through History

The Qur’an repeatedly calls upon believers to contemplate the fate of past nations as a means to deepen understanding and gratitude toward God: “Travel through the land and observe how was the end of those before you.” (Qur’an 30:42)

“Have they not traveled through the earth and seen what was the end of those before them? They were greater in power than them, and they ploughed the land and built upon it more than they have built.” (Qur’an 30:9)

According to Imam al-Ṭabarī (d. 310 AH), these verses command believers to contemplate the āyāt (signs) embedded in human history—not merely as moral parables but as empirical reminders of the impermanence of worldly power and the necessity of faith.¹ Similarly, al-Qurṭubī (d. 671 AH) viewed the Qur’anic call to “travel and see” as an encouragement to learn from the material and moral legacies of earlier nations, linking ʿibrah (reflection) to intellectual and spiritual inquiry.²

This Qur’anic ethos forms the philosophical foundation of the Muslim engagement with antiquity: to observe, to learn, and to extract wisdom—without idolizing or erasing the past.

Early Muslim Encounters with Ancient Civilizations

1. Egypt and the Pharaonic Heritage

When Muslim forces entered Egypt under ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀṣ in 641 CE, they encountered one of humanity’s most ancient civilizations. Far from imposing cultural rupture, early Muslims integrated Egypt’s Pharaonic and Hellenistic heritage within the Islamic civilizational framework.

2. The Abbasid Translation Movement

The Abbasid caliphs, particularly al-Maʾmūn (r. 813–833 CE), institutionalized preservation through the Bayt al-Ḥikmah (House of Wisdom) in Baghdad. Texts of Greek, Persian, and Indian origin were translated into Arabic, initiating a process that both preserved and expanded ancient knowledge.

This ethos transformed the Islamic world into the custodian of global civilization, ensuring that the intellectual heritage of antiquity survived long after the decline of its original societies.

3. Al-Andalus and the Continuity of Antiquity

In al-Andalus, Muslim rulers and scholars engaged deeply with Roman and Visigothic legacies. The Great Mosque of Córdoba, initially part of a Visigothic church complex, came to symbolize the fusion of diverse cultural layers into a single artistic expression. Andalusian thinkers such as Ibn Rushd (Averroes) (d. 1198 CE) not only preserved Greek philosophy but transmitted it to medieval Europe—catalyzing the Renaissance.⁵

This cross-civilizational dialogue illustrates that Islamic civilization viewed preservation as participation in the ongoing story of human creativity under divine stewardship.

Theological Foundations for Cultural Preservation

Three foundational Islamic concepts underpin the moral imperative to preserve human heritage:

- Khilāfah (Stewardship)

Humanity is designated as khalīfah (vicegerent) on earth:

“It is He (Allah) Who has made you successors upon the earth.” (Qur’an 35:39)

- ʿIlm (Knowledge)

The pursuit of knowledge in all its forms is central to Islam. The Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) said: “Seeking knowledge is an obligation upon every Muslim.” (Sunan Ibn Mājah)

- ʿIbrah (Moral Reflection)

The Qur’an states: “Indeed, in their stories there is a lesson (ʿibrah) for those of understanding.” (Qur’an 12:111)

It is worthy to mention that The Grand Egyptian Museum is not merely an archaeological enterprise; it is a spiritual and civilizational act of stewardship—a reaffirmation that preserving the memory of humankind aligns deeply with Islamic theology and ethics.

References

- al-Ṭabarī, Jāmiʿ al-Bayān ʿan Taʾwīl Āy al-Qurʾān, Vol. 21 (Cairo: Dār al-Maʿārif, 1968), p. 33.

- al-Qurṭubī, al-Jāmiʿ li-Aḥkām al-Qurʾān, Vol. 14 (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah, 2006), pp. 22–24.

- al-Maqrīzī, al-Mawāʿiẓ wa al-Iʿtibār bi Dhikr al-Khiṭaṭ wa al-Āthār, Vol. 1 (Cairo: Būlāq Press, 1853), p. 44.

- Ibn Wahshiyya, Shawq al-Mustahām fī Maʿrifat Rumūz al-Aqlām, ed. Joseph Hammer (Vienna: 1806).

- Ibn Rushd, Tahāfut al-Tahāfut (The Incoherence of the Incoherence), trans. Simon van den Bergh (London: Luzac, 1954).

Arabic

Arabic French

French Deutsch

Deutsch Urdu

Urdu Pashto

Pashto Swahili

Swahili Hausa

Hausa